A tale of progress

Chicago's water cribs, and how far we have come in 200 years

In 1854, Chicago killed 6% of its population in a single summer from cholera, a bacteria that spreads through a fun journey called the “fecal-oral route”. The disease itself, however, got here through a river route. The construction of a canal earlier in the century had linked the Chicago river with the Illinois river, which carried goods (and bads, like the cholera) up from New Orleans and established Chicago as a major city along the route towards the Atlantic.

It is often easy to forget the sheer size of fixed cost investment required to make things like indoor plumbing and clean water an afterthought for most people in the developed world. Up until 1920, right before the swing of the roaring twenties and the invention of things like “holding companies” and “Goldman Sachs”, only 1% of households in the US had plumbing. The rest scheduled time to draw water from a well and take their weekly bath on Saturday night, so they could be clean for church on Sunday.

In the midst of such constant frictions in their lives it amazes me that in the 1850s, a combination of scrappiness, ambition, and the need to fix past fuck-ups (that arose from said scrappiness being too scrappy) dug tunnels under the city as deep as today’s skyscrapers are tall and reversed the course of a river.

Act 1: The seeds of death

As a working Chicagoan in the 1850s, the most statistically likely occupation for you would be “common laborer”. Over 30 rail lines were beginning to enter the city, the Illinois & Michigan Canal had just been completed in 1848 and employed thousand, and Irish and German immigrants were pouring into the young city seeking unskilled labor. In that position, you were unlikely to be in one of the few households in the south of Chicago that had wooden pipe systems from the private Chicago Hydraulic Company.

Instead, the water cart vendor is your best friend! They fetch fresh water from Lake Michigan through intake pipes about 600 feet offshore, peddle it from house to house, and sell it at a shilling a barrel. Unfortunately, they were also killing you.

Chicago sat at the southwestern tip of Lake Michigan, where a sluggish river called the Chicago River meandered eastward into the lake. The swelling population, as was the thing people did during the time, dumped its waste into the river to be carried away. The slaughterhouses dropped blood, offal and unwanted carcasses directly into the water. Distilleries, tallow renderers, soap and candle makers all treated the river as a convenient disposal system.

It seems insane to us now, however out of fashion ESG has become, that this could have been a common business practice. But in those days, no alternative infrastructure existed - it was either cesspools (would contaminate groundwater and wells), hauling it away (prohibitively expensive) or dumping it in the street (immediate protest). It was not until 1855 that a sewage system was given any thought or attention in Chicago. Besides, it was a genuine belief that Lake Michigan was so vast that it could dilate any waste to harmless levels.

The dilution did not happen. The lake’s currents would push the contaminated river water back along the shoreline, while rainfall washed waste from the streets directly into the water supply. Between 1849 and 1865, cholera, typhoid and dysentery killed thousands, right on the edge of billions of gallons of clean and cold water. The Chicago Tribune wrote, bitterly:

“With an unlimited quantity of the purest water upon the continent of America, in the closest possible proximity, our city is nevertheless but poorly supplied with facilities for an abundant and cheap supply of the article.”

Act 2: The engineering feat

The solution is obvious, but gnarly in execution. If the water near shore was poisoned, the move was surely to get clean water from miles offshore, in the deep, cold and unpolluted heart of Lake Michigan.

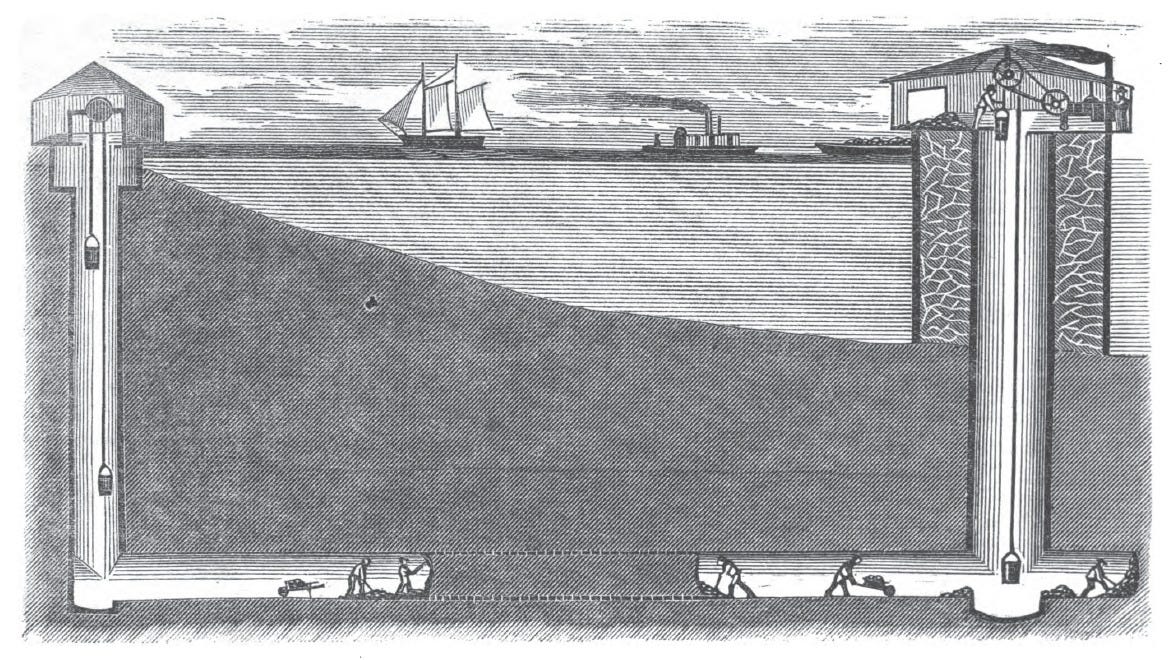

Ellis Chesbrough, the chief engineer, proposed the water crib system. This would link a vertical shaft dropping 66 feet down from the Chicago Avenue pumping station with a vertical shaft rising up through the lake bed to the crib sitting on the lake surface, connected by 2 miles of passage through bedrock. The intake pipes would draw water from 20-60 feet below the lake surface—the “Goldilocks zone” where the water was cold enough to discourage bacterial growth, deep enough to avoid surface contamination and wave action, but not so deep as to hit the thermocline where temperatures drop sharply in summer.

Work began March 17, 1864 at the Chicago Avenue site. Workers dug straight down through layers of clay, sand and water-bearing sediment until they reached bedrock. Once in solid limestone, they began boring horizontally eastward, toward the lake. This was terrifying work. The tunnel was only 5 feet in diameter, which meant men could only stand hunched over. The tunnel had to be lined with brick as they went, creating a tube that could withstand the enormous pressure of millions of tons of lake water pressing down from above.

Meanwhile, work commenced on the other end. They constructed a large pentagonal box using interlocking wooden beams, floated it out into the Lake over a precisely calculated location, and sank it by filling the hollow space between the crib’s double walls with stone rubble. Then, they lowered a massive cast-iron caisson down inside the timber crib structure, where its sharp cutting edge at the bottom helped it penetrate the sediment into the bedrock. Once there, steam pumps removed water from the inside, and workers descended hundreds of feet to mine.

A minor detail, but one that i was terrified by - even when the cutting edge sealed against solid rick, the steam pumps needed to continue running to prevent the workspace from being flooded. This was because the rock had natural fractures and fissures, porous spaces between mineral grains and cracks, meaning that groundwater under presure from the lake above would find these pathways and seep through the rock into the caisson.

Two years later, in November 1866, the two tunnels met. With only picks, compasses and dug by hand in the dark, the tunnels were off… by just 7.5 inches. Insane!

Act 3: Water fortresses

Once complete, the crib themselves had to withstand the ghastly weather Lake Michigan threw at it, storm waves and ice flows, winds and temperature swings. Workers also lived in isolation year-round in the building on the lake, taking week-long shifts. They operated the intake valves and monitored flow rates, cleared debris and dead fish from intake screens, tended the lighthouse and fog bells and prevented ice from blocking the intakes.

Before they installed steam heating plants that kept the well room at a constant temperature even in the depths of winter, workers had to use hand tools like long poles and picks to break the ice manually. Barring that, they used small amounts of dynamite. The balls of steel required to not only live isolated on a dark lake in the Chicago winter, but also to periodically blow up a part of your house that was the only thing keeping you from plunging into said dark lake, is once again insane to me.

Act 4: Reversing the river

By 1867, clean water was flowing into the city again, and the cholera outbreaks diminished. But it was clear that this was just a stopgap measure - as the city grew, it produced more waste, which it steadily dumped into the river and thus the lake, and which would inexorably creep towards the offshore intakes.

Responsible business practices were clearly too much to ask, so instead the Chicago Sanitary District sought to reverse the course of the river.

In 1892, construction began on the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, which cut through the landscape from Chicago to the Des Plaines River. The key here was this: Lake Michigan sits at ~580ft above sea level, while the canal endpoint was precisely engineered to be 574 feet above sea level. The Chicago River, sitting at a junction between these two low points, had its path dictated for it by gravity.

When the canal opened on Jan 2, 1900, the river physically paused, reversed, and began flowing west. And thus away it went.

The legacy of human striving

Going down the rabbit hole of 1800s engineering, I was reminded of Adam Mastrionni’s blog post on the decline of deviance.

In short, he postulated that people are less weird now, less prone to doing illegal things and stepping out of line, because there is more to lose from it as lifespans expand (reputations! teeth that i might want to use later!). This made a lot of sense to me. If I truly thought that my life expectancy was 30-40 years, as is the average for a woman in the 1800s, I would likely choose not to have a child. I would also definitely not contribute to my 401(k). (As is average for a woman in the 1800s, however, both choices would likely not be mine to make.)

I think about this, imagining the life of a common laborer declogging the intake valve 2 miles out in the lake, freezing in the Midwestern winter. People often jest that some piece of media would “kill a victorian child” - I beg to differ. When people emerge from the giant black hole extending down into the ground, just to buy water from the water bucket man that may or may not kill you, before they start their shift on the isolated floating timber platform - I think they’ll be just fine sipping a Four Loko, made today in Chicago using water drawn up from 200-year-old tunnels.

this is so interesting what a fear !! although did they kinda screw over missouri too :")